It has been said of Book VI of the Aeneid, the part of the epic story when the hero, Aeneas visits the underworld, that Aeneas went down to the underworld a Trojan and returned a Roman. Maybe one year, during the twelve days, I’ll write my thoughts on each of the twelve books of the Aeneid. Instead, I’ve chosen to translate twelve selected passages of Book VI. I’ve decided to do this because indeed, Aeneas is transformed by his visit to the underworld and my meditations try to be about change. The selections are driven by interest in the scene, the Latin, and because the passage has something interesting to me at this time of ending and beginning.

We all could use a visit to our own underworld. Dante’s visit to the underworld in the Divine Comedy is inspired by Book VI, especially the vivd descriptions of the punishments in the various regions of the world beyond the River Styx. My annual reflections during this period are always attempt at self-reflection, and Book VI is the place where the hero goes from an Odysseus like wandering to a more determined effort and fulfilling his destiny, even while that destiny consumes many good people.

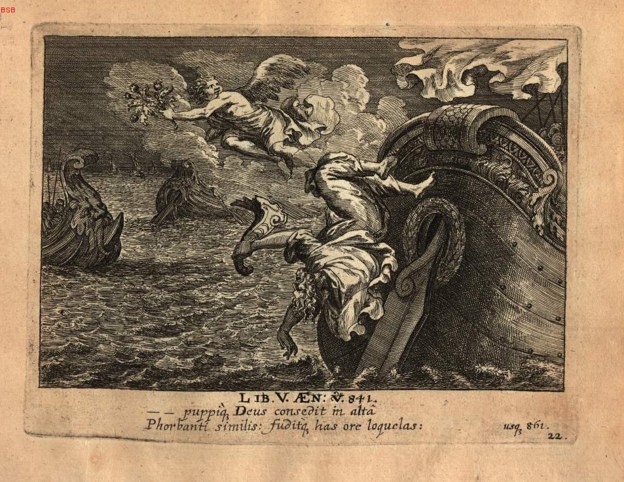

Book VI begins with Aeneas weeping over Palinarus, who is lulled to sleep at the controls of the ship and falls into the sea and drowns. Palinarus is one of many noble, and good characters that seem to suffer either needlessly or because they somehow step in the way of the destiny, the fate of Aeneas. After Palinarus death, the Trojan ships find their way to their destination anyway, but Aeneas is still struck by the loss of his loyal helmsman at the end of Book V.

“O you, Palinurus, Who trusted in the calm of sea and sky,

You will lie naked on some unknown shore.”

“O nimium caelo et pelago confise sereno,

nudus in ignota, Palinure, iacebis harena!”

The translation is from David Ferry, my favorite translation.

However, Seamus Heaney completed a translation of Book VI more than a decade ago, and his translation of that book is the one that has inspired this effort. I’ll always cite Ferry or Heaney when quoting them. I am also going to rely on Nicholas Horsfall’s commentary.

I don’t have much room (this has gone on much longer than usual) to do much explication of the text, but in a way, that’s not the point. This is, as usual, a meditation, intended to do whatever it is supposed to do, to arrive like the boats at the beginning of Book VI at it’s end, at some “littora curvae” yet unknown.

Virgil’s Latin text is always first, followed by my translation. My meditation will be no more than 100 words following my translation. The citation of the Aeneid is book number, and lines, from H.R. Fairclough’s translation in the Loeb Library (the little red books).

Second Day: “Raving Winds Around Her Blowing”

Fourth Day: Tooting Your Own Horn

Seventh Day: I’ll Be Right There

Eighth Day: Oh Boy, Here We Go.

Tenth Day: Would You Please Please Please Please Please Please Please Stop Talking