Let’s go back, let’s go back

Let’s go way on, way back when

I didn’t even know you

You couldn’t have been too much more than ten (just a child)

I ain’t no psychiatrist, I ain’t no doctor with degrees

But, it don’t take too much high IQ’s

To see what you’re doing to me

You better think

Aretha Franklin

I have somewhere between 200 and 300 pages of fiction writing to edit. I call it “The Story,” and it’s been through several edits and it’s time to get it done. However, I keep finding things to delay me; the latest is a study of two historical and literary figures, Dido and Margaret. Dido is Aeneas’ love interest in the Aeneid, and Margaret is Henry’s Queen in Shakespeare’s Henry VI, parts 2 and 3.

Of course, there is more to these women than their association with these men. Dido steals Book IV of the Aeneid in such a powerful way as to make the epic distracted enough that we, like Aeneas, forget the whole point of the story, founding Rome. And Margaret is hardly Henry’s Queen, but he her King, an ineffectual and weak one, more a burden to her power than anything else.

Why Dido and Margaret?

The female character in The Story is a woman who discovers the truth about herself and family, and sets out to learn more about them and who she is. She encounters a man running the opposite way, seeking distance from where he came so he could rebrand himself. They crash into each other. That’s The Story.

I’m fascinated by Dido and Margaret, especially moments when they excoriate their male opposites. The Story honors, I think, female anger and disappointment in men. In particular, my main female characters are let down by men in the old familiar way. Why I find this theme compelling is probably obvious. I’ve let down plenty of women while at the same time been blessed with more strong, powerful, intelligent, and prescient women than I deserve.

I suppose some might find some misogyny in this appreciation. Maybe. But women have been my role models, heroes, and often, patient partners I haven’t deserved. My grandmothers still give me strength even though they are dead. And Bernadette Devlin and Margaret Thatcher are still guide stars for me even though they are polar opposites; each of them dominated men as women playing by men’s rules.

The character in my story is influenced by these women. She is consciously modeled on Dido and at one point in the story, she repeats the line that Queen Margaret deals to Henry in Henry VI, “Thou hast undone thyself, thy son and me.”

Dido issues a scolding to Aeneas when he ties to tip toe out of Carthage to found a new Troy: “O faithless! Did you think that you Could hide this deed from me, and steal away?”

Two Queens, two Kings, two strong women and two men failing to meet the moment. That’s why Dido and Margaret.

The Works and the Women

The Aeneid

The Aeneid is an epic poem written by Virgil about 19 BC as propaganda for Augustus, a newly powerful Roman Emperor. Augustus transformed Rome into what we think of it today in contemporary culture. He enlisted Virgil to write an origin story of the Roman Empire he inherited and expanded. The result was the Aeneid.

The genius of the Aeneid inhabits many levels. For this, its shadowing of Homer is worth mentioning. Virgil creates Aeneas as a leader of a group of refugees from the burned down Troy (remember the Trojan horse from the Iliad?), wandering (like Odysseus and Jason) from one messed up situation to the next. Anchoring the origins of Rome in Homer’s epics is like adding an episode to the Star Wars series; it gives the story a kind of cultural legitimacy.

While the Aeneid was popular and has worked its way into many elements of our common cultural language, Homer is far more familiar to most people in the west today than Virgil.

Dido

Dido is mostly considered a legendary figure, mostly known through Virgil’s Aeneid. Her origin story in the Aeneid is that she was Queen of Tyre, geographically known today as Lebanon, also known as Phoenicia. She was married to Sychaeus who was killed by her envious brother, Pygmalion, precipitating her exit on the seas and landing in North Africa where she founded Carthage in today’s Tunisia.

Much has been researched and written trying to determine Dido’s historicity, but what we do know is two things: the Phoenicians ruled the Mediterranean for a thousand years before the emergence of Rome and Greece and Carthage was a real empire that almost displaced Rome as the regional and global power in the Punic Wars.

Aeneas and the reader are introduced to Dido early in the epic.

Because [her brother’s] tyranny, or feared him for it,

Led by a woman came together to act In this enterprise.

Ships in the harbor that were

Already rigged for sailing were seized and loaded

With treasure, Pygmalion’s wealth.

They sailed away

Dido is no cowering flower. She is a tough, calculating woman who, when she realizes her brother’s treachery – killing her husband – leaves town with all Pygmalion’s money. I think, maybe, one of the most beautiful sounds in Latin is,

Portantur avari Pygmalionis opes pelago;dux femina facti

All of the greedy Pygmalion’s money is carried off on the sea; a woman did this (my bad translation).

Henry VI, Parts 1, 2, and 3

The War of the Roses, a dynastic battle over the throne of England, began in the 14th century when a weak king, Richard II, was deposed by a stronger, more aggressive relative, Henry IV. It would be anachronistic to say Richard was a “York” (White Rose) and Henry was a Lancaster (Red Rose), but it helps sort out the following 150 years of civil wars framed by a hundred year long war with France

I’m not going to get into the family tree or the feud other than to say that by the time Henry IV grandson took the throne, as a baby, the world had changed. Henry VI grew up under the close watch of his uncle, the Duke of Gloucester. Henry never found his voice or his personal power, and when it came time to marry, his wife, Margaret of Anjou would overwhelm him.

In the end Henry would bargain away his power, get it back again, and die, in revisionist Lancastrian history, as a saintly king. His weakness and indecisiveness during a period of foment led to many others replacing him as most powerful in the realm; the most significant of these for this consideration is his wife, Margaret.

Margaret

Margaret was like so many girls of royal birth that were played like game pieces in larger regional power plays. She was not a great catch. In fact, she had no dowery, and came with a lover in tow, Suffolk, who manipulated her selection of his lover Margaret into what he thought would be his own ascendance to the throne, or at least his control of it.

The 16th-century historian Edward Hall described Margaret’s personality in these terms: “This woman excelled all other, as well in beauty and favor, as in wit and policy, and was of stomach and courage, more like to a man, than a woman.”

The Paston Letters, quoted by Patricia-Ann Lee, in Reflections of Power: Margaret of Anjou and the Dark Side of Queenship gives us another contemporary picture of the Queen: “The Quene is a grete and strong labourid woman, for she spareth noo peyne to sue hire thinges to an intent and conclusion to hir power.”

The Milanese ambassador, quoted by lee, describes Margaret as a “most handsome woman, though somewhat dark.” One wonders whether this referred to her complexion or disposition; I’d like to think it was both. Either way, mi corazon es tuyo.

Dido’s Lament

But the queen (for how can one who is in love

Be kept deceived?), having already been

Fearful when there was nothing to be feared,

Divined [Aeneas’] secret plan, becoming aware

Of this activity that was underway;

And heartless Rumor whispered to her the news

That the fleet was being armed and prepared for sailing.

At regina dolos—quis fallere possit amantem?

Praesensit, motusque excepit prima futuros,

Omnia tuta timens. Eadem impia Fama furenti

Detulit armari classem cursumque parari.

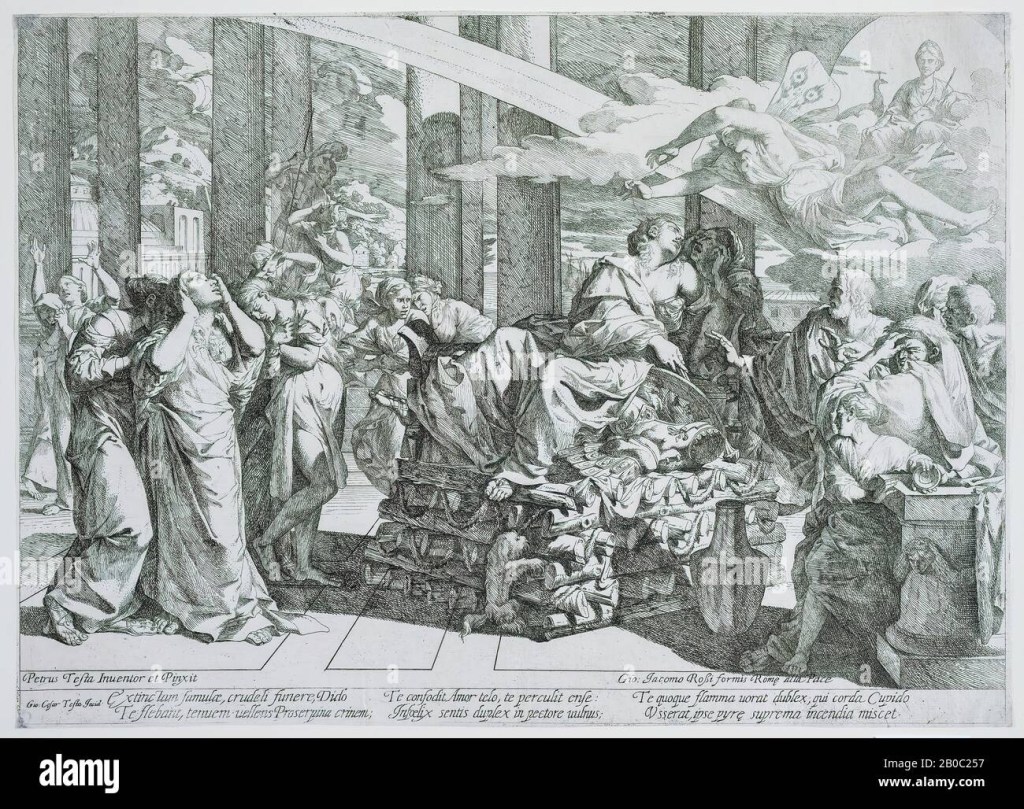

Book IV of the Aeneid can be divided into three parts, each one beginning with the phrase, “At regina,” or The queen. It indicates the central nature of Dido in Book IV at least, and that she’ll be remembered forever. The music of Book IV depends on this repetition of “at regina.” We hear it at the beginning of the book, “At regina iamdudum” when she is stricken with love for Aeneas, here as she becomes outraged at Aeneas, then once more, “At regina, pyra penetralia,” when we see Dido piling up her symbolic immolation (Gildenhard)

Rumor here is absolutely central. Rumor appears first in Book IV right at the moment that Dido and Aeneas get together in the cave. “Fama per urbes.” It matters that rumor, personified in the Aeneid as a flying, many eyed beast, is fama in Latin, a word that sounds like the English word fame. Rumor flies around alerting Dido’s jilted suitors that’s she’s hooked up with Aeneas.

One of them, Iarbas, sends a plea to Zeus, who stirred from whatever else he was doing, gets irritated. What the hell is Aeneas doing messing around with this woman? It moves the plot along when he sends Mercury down to get Aeneas to abandon Dido. Fama appears here again to let Dido know that Aeneas is planning to slip away. Later, Dido will refer to stirred up Iarbus as one of her pleas for Aeneas to stay.

The news was maddening; Dido was like

A Thyiad undone, aroused, on fire,

In frenzy, by the sound of the emblems shaking

In rage in the dance around the city, burning,

Inflamed by the noise of the Bacchic orgy and

The clamoring on Mount Cithaeron in the dark

Of the night.

How mad is Dido? As mad as a Thyiad undone. What is a Thyiad? The Thyiades are women attached the nymph Thyia, who was the first to honor Dionysus with a sacrifice. The Thyiades would celebrate and sacrifice to Dionysos at her shrine. There was a kind of possession associated with these celebrations in which the women became ecstatic. The reference would be familiar to a Roman audience, and according to Estevez it “almost always involves Pentheus and Thebes.”

Pentheus was a king of Thebes who banned the celebration and veneration of Dionysus. The god, enraged, possessed his Pentheus’ mother and other women of Thebes. Pentheus pursued Dionysus and tried to imprison him. Dionysus disguised himself as a woman and lured Pentheus to go out to hide in a tree watch some women hoping to see some sexual activity.

But when the women, in their possession, thinking Pentheus was an animal, tore him to shreds. His own mother among the women put his head on a spike and returned to town touting as if it was an animal’s head. Only when she sobered up from her possession did she realize it was her own son.

I have struggled for many minutes on a reference that would resonate with a contemporary audience the way this one would for Romans. This is the best I could think of, Ripley blowing the Alien out of the airlock.

The context is completely, different of course. But Ripley is a powerful woman who has had enough. A reference to Ripley and the “air lock scene” would conjure the image of a woman that is about to kick someone’s ass.

In this context, it’s hard to imagine that a Roman audience wouldn’t think, “Oh shit! She is really pissed. I wonder what she’s going to do to him <eats more popcorn>” The target of this “fire” and “frenzy” is Aeneas. Virgil, I think, wants to dial up the scene with the sense that she might just punch him in the face or worse.

She is indeed about to throw everything she has at him. The scene begins with her rage at Aeneas, he responds, and then she unleashes more words. I’ve divided this opening into three parts. The first part is Dido appealing to Aeneas’ sense of loyalty and obligation. What’s compelling about Dido’s response is that in this instance, she is not critical of Aeneas as much as she is trying to persuade him not to leave her.

These are the words she spoke to him,

Accusingly: “O faithless! Did you think that you

Could hide this deed from me, and steal away?

Cannot our love keep you from doing this?

Cannot your plighted word keep you from this?

Cannot the thought of the death you would leave me to,

Keep you from this? Now you are making ready

Your fleet to go out on the winter seas in the teeth

Of the Aquilonean storms. O cruel! If Troy

Were still unfallen, and you, if you were not

Seeking for alien fields and unknown places

To make your dwelling in, you would not, would you,

Set sail to Troy with your Trojan fleet in such

Tempestuous seas?—But is it I that you

Are fleeing from? I, by my weeping, and by,

Since nothing else in my misery is left,

The promise made by your right hand and by

Our marriage and our vows, and if there was ever

Anything that I deserved from you

By any sweetness that I brought to you,

Have pity on my tottering house, I pray

And if there is any room in your heart for prayer,

Abandon this that you are about to do.

She starts the way a woman in this position might. “You thought you were so smart that I wouldn’t know.” In a way, she starts with her hands on her hips. Maybe pacing back and forth, perhaps possessed not like a Thyiad, but with rage not only at him for leaving but at herself for having allowed herself to be in this position. The appeals to logic. If Aeneas wasn’t on some fantastical tour of the Mediterranean, he wouldn’t expose himself to rough seas. He wouldn’t do that even if Troy was still standing and he just wanted to go home.

I can imagine a staging that would have her stop, lean forward pointing to her chest with tears welling in her eyes, and screaming, “But is it I that you are fleeing from?” Then she plays the cave card. Remember that night in the cave you bastard, don’t you remember our marriage vows? We were not in the cave. Virgil doesn’t give us any dialogue or anything explicit about what was said in the cave, but in heat of passion who knows what was said.

“You love me, don’t you?”

“Yeah, sure baby,” Aeneas might have said. “Yes, I do.”

“This means it’s forever, right?”

“Of course, honey,” Aeneas might have said. “Whatever you want.”

You can see where I and Dido are going here. Aeneas is an asshole, making promises in the cave that he would not and could not keep. Perhaps one might even make the leap that there was a false pretense and promise made in exchange for Dido’s violation of something she really held dear, her loyalty to her murdered husband. Did Aeneas rape Dido? I’m not the first to think that. And I really believe that Virgil wants his audience to see what happens in the cave as dark – it’s in a cave after all, and he conceals what happens with purpose.

Right after their time in the cave, Virgil foreshadows its implications.

That day was the cause of the death to come, the cause

Of calamity, for Dido was no longer

Inhibited by the restraints of keeping her love

A secret from others; she covered over her shame

By calling the deed they did together a marriage.

Was this shame because she’d been taken advantage of, lied to get something in the moment? Or is this the idea that even though he is dead, Dido was sort of cheating on her dead husband, Sychaeus who was murdered by her brother Pygmalion precipitating her flight to North Africa. Certainly, Dido thinks something like this. At the opening of Book IV, she’s clearly worried about Sychaeus saying she’d rather go to hell, calling out to Chastity not wanting to “violate your laws.”

He, who joined my heart to his and took it

Away with him to the grave, I pray that he

Will keep it where he is and guard it there.

Anna, her sister dismisses this. C’mon, Dido, you’re lonely, he’s good looking and strong, and he’s here. And there’s Carthage to think about too. “With Teucrian arms beside us, to what heights will Punic glory soar?”

And appropriately, in her tongue lashing of Aeneas, her thoughts shift to “the cause of calamity” described earlier. The second part of Dido’s rage is directed at the direct consequence of the illicit cave scene transported to Iarbus, a local suitor of Dido she had resisted. Everything was fine, but now Iarbus was enraged that after being put off, she’d hook up with the shipwrecked Trojan.

It’s worth noting too, that the Loeb translation by Faircloth translates this (miserere domus labentis et istam) as “pity a falling house.” Ferry’s translation (which I’m using throughout) translates this as “tottering house.” The Faircloth uses this word, “tottering” when Dido describes that Aeneas alone is the only one who has caused her to feel like giving up on Sycheaes. Solus hic inflexit sensus animumque labantem impulit, is translated by Faircloth as “He alone has swayed my will and overthrown my tottering soul.” Ferry translates that, “only this person has disturbed my sense of who I am, and made my purpose totter in uncertainty.”

Ferry does things on purpose, and so is calling us back to that moment and it’s a rich little thing to find in his translation, and hard to miss if looking closely. Dido’s tottering soul means she’ll fall in love with Aeneas after the cave, but now it’s her house, her empire, that it is threatened, something that will put Dido in a terrible spot.

It is because of you that now I’m hated

By the Libyan and the Numidian lords, and by

The Tyrians turned against me. I have been shamed,

And I have lost my honor, the fame that was

To be carried up to the stars. To what am I

Abandoned, dying, by this alien guest?

For guest is the name that is all that’s left of husband.

Why am I staying here? Until my brother Pygmalion takes my city?

Until Gaetulian Iarbas takes me captive?

Dido and Carthage are surrounded by wolves, Iarbus, other suitors, and even her brother who might still find her. She has done a fine job of keeping the locals at bay with a balance, perhaps, of guile and Penelope like delaying tactics. And here’s the thing, something that Dido hammers on later, she rescued Aeneas. “Guest (hospes) is all that’s left of husband.” I think this is a poignant moment, maybe referring to both Sychaeus and Aeneas. The idea of husband is really the reality of transience; no man will ever stay.

Translation is interesting here too. Faircloth renders the line, “You leave me on the point of death, guest – since that alone is left from the name of husband.” I am not enough of a Latin scholar to parse this, but I think I might prefer the dramatic and dripping sarcasm that Dido could ladle on the word in Faircloth’s version rather than Ferry’s rhetorical version.

Then, the third and final phase of this lashing out, Dido says something apparently desperate.

If at least before

You left you had left a child with me—if only

An infant Aeneas, whose face would remind me of yours,

I would not feel so deserted and overthrown.” She was silent.

This ends the first part of her tirade on a note of pathos uncharacteristic of the tenor of the rest of it. T.R. Bryce considers different views on this in “The Dido-Aeneas Relationship: A Re-Examination,” including “cloying sentimentality,” that a baby “would at least give the impression that Dido’s and Aeneas’ union has an official basis,” or “mere ploy, a delaying tactic.” Bryce rejects these, favoring the view that a child would have somehow validated what she had lost in the cave, a reparation of sorts. Maybe that’s not exactly Bryce’s view, but I think it’s close and it might be close to my view as well.

I think Virgil is an agile story teller, and whatever else he is doing and trying to do in the Aeneid, his characters are stunningly human. Here, Dido is expressing a sentiment that is typically human; a child can be the externalization of a mix of internal desires ranging from saving a relationship to attaining some kind of immortality. Whatever her desire, it’s probably mixed, and her change in tone strikes me as something that puts her an excessively vulnerable position emotionally and it humanizes her. And it makes her sympathetic in the face of what appears to be Aeneas’ carelessness and confusion about where he is and where he is going.

Margaret’s Rebuke

As noted above, William, the Duke of Suffolk while fighting the French happens upon Margaret and falls in love with her. But his design is to both have her, and to marry her to King Henry knowing that if he captures her heart – or at least her imagination – he can have Margaret and rule the King and the Kingdom through her.

Once Suffolk is dead, however, Margaret continues her ambition to rule Henry and the country. And, once she has a son, she can continue to rule through him no matter what happens to Henry. But the ghost of Richard II wanders through all of the Henry plays as does the questionable claim Henry’s grandfather, Henry IV, had to the throne.

Richard the Duke of York has a much better claim to the throne. As Henry’s misgovernment causes loss after loss on the continent, some lords band around York and threaten to overthrow him. They raise the dubious claim of Henry IV and threaten Henry with disposition. Henry folds. Warwick stamps his foot, and that’s all it takes to let out a sigh and capitulates.

WARWICK

Why should you sigh, my lord?

KING HENRY

Not for myself, Lord Warwick, but my son,

Whom I unnaturally shall disinherit.

But be it as it may. (⌜To York.⌝) I here entail

The crown to thee and to thine heirs forever,

Conditionally, that here thou take an oath

To cease this civil war and, whilst I live,

To honor me as thy king and sovereign,

And neither by treason nor hostility

To seek to put me down and reign thyself.

Henry is either a coward, refusing to defend his claim to the crown he wears, or a pacifist, genuinely worried about more bloodshed. Some scholarship might suggest an interpretation that he could be both. Either way, he keeps himself in power, but pays for that and peace by denying his son the throne. But worse, he kneecaps Margaret. His actions are certainly thoughtless, but also raises the ghost of Richard again; Sarah Pagliaccio quotes Samuel Johnson who wrote, “the loss of a King’s power is soon followed by the loss of his life.”

When Margaret finds out that the weakness of her King which enables her power has caused him to disinherit her son and her, she is furious. In a moment, Henry has undone all the work she has done with Suffolk and on her own to build power for herself and to ensure her son’s place. The men around the King can feel her presence before she even arrives. Here is her take down of Henry.

EXETER

Here comes the Queen, whose looks bewray her

anger.

I’ll steal away.

KING HENRY Exeter, so will I.

⌜They begin to exit.

Enter Queen ⌜Margaret, with Prince Edward.⌝

The image, as Pagliaccio notes, is somewhat comical. Here comes the angry wife, child in tow, to yell at the errant husband who has perhaps stayed at the bar too long or purchased another expensive toy. The Aeneid opens with “I sing of arms and the man,” but the narrator also sings of “Juno’s Savage implacable rage.” In this case, the men, including Henry try to scatter like cockroaches before a Margaret ready to stomp on them.

QUEEN MARGARET

Nay, go not from me. I will follow thee.

KING HENRY

Be patient, gentle queen, and I will stay.

Pagliaccio points out an earlier request by Henry in Henry VI, Part II, when Henry says, in the face of opponents closing in, “Can we outrun the heavens? Good Margaret, stay.” Henry in the plays is a man who feels doomed. One way to view this is that he has a saintly respect for God’s will; another is that he is simply passive, weak, and even lazy. Margaret won’t have it.

QUEEN MARGARET

Who can be patient in such extremes?

Ah, wretched man, would I had died a maid

And never seen thee, never borne thee son,

Seeing thou hast proved so unnatural a father.

Hath he deserved to lose his birthright thus?

“Just relax, honey,” Henry is saying. And he has the gall to put it terms of a negotiation. I won’t run from you and from accountability if you’re nice to me. She cuts right to it, she wishes she wasn’t even here, that Suffolk had never wooed her to him and attached her to such a weakling. Margaret is conflicted of course because she would not be as powerful as she is if he were not so weak. Patricia-Ann Lee writes “it is intriguing to speculate about the pattern of Margaret’s life and the fate of her reputation had she married a different kind of man.”

Perhaps Suffolk? But Suffolk was a sociopath at least if not diabolical, bent on power without accountability. Lee is right that Henry was “weak, inept, and finally, mentally ill” and “could not himself deal with his court or with the general governance of the realm.” I’d like to think Margaret would have kicked his ass anyway.

She continues.

Hadst thou but loved him half so well as I,

Or felt that pain which I did for him once,

Or nourished him as I did with my blood

Thou wouldst have left thy dearest heart-blood

there,

Rather than have made that savage duke thine heir

And disinherited thine only son.

I’m going to hold off on a comparison here with, “saltem si qua mihi de te suscepta fuisset ante fugam suboles, si quis mihi parvulus aula luderet Aeneas, qui te tamen ore referret, non equidem omnino capta ac deserta viderer.”

But Margaret drills in that Edward, their son, is part of her, nourished “with my blood.” She cites the pain of child birth. Again, I’ll come back to it, but is Margaret being maudlin here, appealing like Dido might have been, to a male desire to have and protect progeny? Is this real or just a tantrum, a show?

PRINCE EDWARD

Father, you cannot disinherit me.

If you be king, why should not I succeed?

I’m sorry, but I would have cut this and would from any production. I might have substituted it with a stage direction, [Edward runs to his father and embraces him, Margaret reaches for Edward and pulls him away.] Edward in this scene is better seen and not heard and that pathos would be better demonstrated by action than stilted dialogue

Then Henry goes into full complain and explain mode, not unlike Aeneas does at the end of his scolding.

KING HENRY

Pardon me, Margaret.—Pardon me, sweet son.

The Earl of Warwick and the Duke enforced me.

This sets up Margaret well. It’s not my fault, Henry implores, they made me do it. I’ll get back to it later, but it’s the same thing Aeneas does. In this case, agency is abandoned by the man in favor of externalities.

QUEEN MARGARET

Enforced thee? Art thou king and wilt be forced?

I shame to hear thee speak. Ah, timorous wretch

I savor this part of her speech. Henry has simply laid himself prone to be done away with. You are King. That means you are God’s anointed. All powerful. More importantly, you are a man. Here, I think Margaret destroys Henry forever and ever. As a woman, she has taken power through men. Suffolk is strong and powerful. Henry weak and pliable. But what I hear her saying is, “Give me a fucking break! You’re a man. You are born with this power. Society has given it to you. Look at me you pathetic loser! I’m a woman. She returns to this theme soon.

Thou hast undone thyself, thy son, and me,

And giv’n unto the house of York such head

As thou shalt reign but by their sufferance!

To entail him and his heirs unto the crown,

What is it but to make thy sepulcher

And creep into it far before thy time?

Warwick is Chancellor and the lord of Callice;

Stern Falconbridge commands the Narrow Seas;

The Duke is made Protector of the realm;

And yet shalt thou be safe? Such safety finds

The trembling lamb environèd with wolves.

I think this is among the best language Shakespeare ever invented. You’ll only be in charge with their (the York’s) permission, which really isn’t being in charge at all. You have dug your own grave, and you will creep into it, like a loser, before your natural life. Animal references are rife in the Henrys, and this one is beautiful; one trembling lamb surrounded by wolves licking their lips.

This harkens back to Richard II, and it is interesting to think that Henry VI parts 2 and 3 were written about 5 years before Shakespeare wrote Richard II. One can easily find an appropriate and perhaps brilliant resonance between both hapless but “holy” kings. Margaret digs in again.

Had I been there, which am a silly woman,

The soldiers should have tossed me on their pikes

Before I would have granted to that act.

But thou preferr’st thy life before thine honor.

Margaret returns to the idea that as a woman, she’s nothing. As a woman she only has status, formally, through her man. Yet, she has greater honor, greater strength, and more determination that this “timorous wretch” and “trembling lamb.” We might be used to this now, but the play establishes Margaret as the paragon of the woman beyond man and woman, a figure that for her own survival and that of her child, must do whatever she has to do regardless of her formal station. That line, “thou preferr’st thy life before thine honor” is a goad, a stab. Men are supposed to value honor more than anything, yet here I am, a woman, with your son, and you are sheltering the one thing that doesn’t matter at all: your pathetic life.

And seeing thou dost, I here divorce myself

Both from thy table, Henry, and thy bed,

Until that act of Parliament be repealed

Whereby my son is disinherited.

All I can think of here is Dua Lipa‘s IDGAF.

So, I cut you off

I don’t need your love

‘Cause I already cried enough

I’ve been done

I’ve been moving on, since we said goodbye

I cut you off

I don’t need your love, so you can try all you want

Your time is up, I’ll tell you why

You say you’re sorry

But it’s too late now

So save it, get gone, shut up

‘Cause if you think I care about you now

Well, boy, I don’t give a fuck

That feeling continues.

The northern lords that have forsworn thy colors

Will follow mine if once they see them spread;

And spread they shall be, to thy foul disgrace

And utter ruin of the house of York.

Thus do I leave thee.—Come, son, let’s away.

Our army is ready. Come, we’ll after them.

KING HENRY

Stay, gentle Margaret, and hear me speak.

QUEEN MARGARET

Thou hast spoke too much already. Get thee gone.

KING HENRY

Gentle son Edward, thou wilt stay ⌜with⌝ me?

QUEEN MARGARET

Ay, to be murdered by his enemies!

PRINCE EDWARD

When I return with victory ⌜from⌝ the field,

I’ll see your Grace. Till then, I’ll follow her.

QUEEN MARGARET

Come, son, away. We may not linger thus.

⌜Queen Margaret and Prince Edward exit.

Margaret isn’t about idle chatter or full of bluster. She does raise an army and mocks and drives a knife herself into a rival. She motivates troops of soldiers who fight for her. She rules, reigns, and though ruthless, has but one goal in mind; the survival of herself and her son.

Perhaps the best line of all that sums up Margaret, as a villain or hero, is how York describes her.

She-wolf of France, but worse than wolves of France,

Whose tongue more poisons than the adder’s tooth:

How ill-beseeming is it in thy sex

To triumph like an Amazonian trull

Upon their woes whom Fortune captivates.

But that thy face is vizard-like, unchanging,

Made impudent with use of evil deeds,

I would assay, proud queen, to make thee blush.

Dido and Margaret, I Love You

These two speeches suddenly seemed to align one day when I thought of them. Before I edit the final version of The Story, I thought, I need to do an analytic comparison of these two speeches. Angry women yelling at men.

Guy Clark wrote a song called My Favorite Picture of You. Here’s a transcript of him talking about the picture and the origins of the song.

This is my favorite picture of my wife, Susannah. Me in Townes were in that house, drunk off our ass, being totally obnoxious, you know, and she’d finally had enough and said, “Fuck you, guys, I’m leaving!”

And I think John Lomax was outside and he took that picture of her and for some reason that has always been my favorite picture of her.

The song is brilliant.

It’s hard to believe

We were lovers at all

There’s a fire in your eyes

You’ve got your heart on your sleeve

A curse on your lips, but all I can see

Is beautiful

I can see myself, Guy, Henry, and Aeneas at the bar sharing our stories.

From an amateur’s perspective, I see many things in common in Dido and Margaret. Both were pulled away from their homes and their countries. They found themselves in foreign territory. In Dido’s case, she was a refugee, running from an abusive and maniacal brother but also dealing with typical men trying to get together with her.

Margaret had to make the best of a political marriage with a foreigner, living in a country hostile to her origins. She wasn’t in love with the one she married but someone else. She found herself with a weak King. Like Dido, she herself was foreign woman in a man’s world forced to survive or perish.

Both were dealing with men who had a sense of destiny or fate. In Dido’s case, Aeneas was supposed to be on his way to founding Rome, although he wasn’t all that enthusiastic about it. Whether he was in love with Dido or just plain lazy, I don’t know, but I think I tend toward the latter. The guy was sort of falling to the top.

Aeneas falls back on his destiny when he’s caught trying to slip out of Carthage.

If fate had left me

With power to follow my own free will and put

My cares in order, the first would be my Troy

And its dear surviving remnant. Troy would still stand,

Would still be there; and I would raise up again

A new Pergamus to protect my vanquished people.

But Grynean Apollo has ordered me

To go to Italy, the Italy of His Lycian oracles, and take possession.

That destiny, that country, is my love.

Henry, as I quoted him above, doesn’t think “we can outrun the heavens.” In fact, his prayer, which I often recite is,

“Lord Jesus Christ, who has created me, redeemed me, and brought me here where I am, thou knowest what to do with me; do with me according to thy will with mercy.”

Both women encounter men who do not have a strong sense of their own agency, or at least do not embrace their own agency. In the case of Aeneas, there is a case to be made that he is the first douche bag; a guy more concerned about detailing his car than taking care of the people around them and their practical and emotional needs. I think in many ways, Aeneas’ frailty is what makes him a hero. Yet, his weaknesses and cluelessness, and maybe even his treachery, are illuminated by Dido, a far more noble character than he is.

As for Henry, it might be possible to see him as an entirely honest soul, aiming to calm things down. But his inattention and lazy deference to those around him enables their treachery, unleashing years of chaos and war. He is not a strong leader, and the vacuum he creates gets filled. Margaret does what she has to do, and fills that void.

Then there is little Edward and Ascanius. Edward is heir to the throne and Margaret’s key to sustainability in her tumultuous world. If she can ensure her son’s right to the throne, they will both be ok. Ascanius is Aeneas’ son, but Cupid disguises himself as Ascanius and works his magic at Venus’ behest. Dido wishes she and Aeneas had a son which would do for her what Edward could do for Margaret. In both stories, the son – real or wished for – mattered. For Dido, the deception of Cupid as Ascanius captured an otherwise strong, principled woman’s heart; for Margaret, little Edward was the embodiment of a promise a weak King couldn’t keep.

I am fond of both Dido and Margaret and feel like I know them each. They recall my grandmothers. My mom’s mother Donelia had 9 kids and more pregnancies than that. So did my dad’s mom, Emma. Neither of them ever wore pants, had a driver’s license, or had what would be called a job. Donelia was born in a state, New Mexico, that was 3 years old; Emma, born in 1907, lived her first 5 years in a territory.

Neither of my grandmothers should have had any power or influence over anything. Yet each of them shaped and formed 18 human beings who in turn shaped dozens more. When they walked into a room, that room changed. They had presence. When they spoke, people listened. When they were silent, there was concern. They looked fragile, but weren’t. There was a determination and strength that could not have come from anywhere but from within.

What I realize is, of course, we’re surrounded by Didos and Margarets and Donelias and Emmas. Strong women, every day, for thousands of years have made the world work in spite of weak, lazy, ineffectual men chasing a big dream. It may seem quaint or even sexist, but I am fortunate to have had many strong women in my life. The character in The Story would be the first to deride and pile derision on this whole effort. She’d be right, of course.

Oh, and your arms are crossed

Your fists are clenched

Not gone but going

Just a stand-up angel

Who won’t back down

Nobody’s fool, nobody’s clown

You were smarter than that

Epilogue

Dido immolated herself after stabbing herself with Aeneas’ sword. She reappears as a silent ghost in Book VI when Aeneas visits Hades. Aeneas calls out to her, but she returns to the ghost of Sychaeus and disappears. The influence of the Aeneid on Dante’s Divine Comedy is inestimable, but one can’t avoid but see the connection especially when Aeneas sees Dido in Hades.

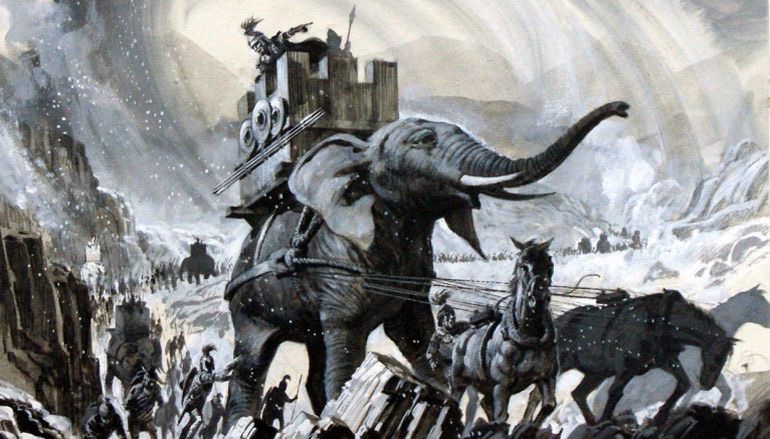

But Dido’s legacy was also Carthage, a city that became a powerful empire. And one cannot forget that without the wronged Dido, there could have been no Hannibal. At least in a dramatic reading of history. Whether Dido really lived or not, Hannibal despised the Romans and vexed them in the extreme. I’d like to think that the Dido’s ghost was there with him as he climbed the Alps with his elephants and massacred the Romans at Cannae.

Margaret’s battle for the house of Lancaster ended in defeat and her son, Edward, was killed. She died in exile and in poverty in France ransomed by her relative the King. Richard III would ascend to the throne under dubious circumstances. Margaret who managed a kingdom and commanded armies would end her life in obscurity. Except that Henry VII, for the House of Lancaster, would defeat Richard at Bosworth and marry Elizabeth of York to end the War of the Roses and create the Tudor Dynasty.

Without the Tudor’s, the modern world we know today would not exist. The evolution and success of Parliament was assured by Henry’s need for it to legitimize his taking of the throne by force. His innovations in government created a bureaucracy around the King that would balance itself against the legislative functions of parliaments thus giving us the first rays of light of what we’d call representative democracy. Again, more a dramatic reading, but now see Margaret’s shade over Henry; how could she not be having a good last laugh.

I couldn’t help but think of these two men, Hannibal and Henry, and the need to close this long trip through the text to acknowledge what I see as their debt to Dido and Margaret respectively. If nothing else, it feels right to say that in a deeper sense, the defeat of these women in one place in history and narrative was redeemed somewhere else by men only because, as women, they did more than exist; they resonated with and shaped the world around them.