On the afternoon of March 15, 44 BC, Julius Caesar made his way to the Senate. Hungover from a night of drinking with Antony and Lepidus, he had initially wanted to cancel the meeting. Persuaded otherwise, he made his way to the Senate where he sat in his assigned position. A group of senators surrounded Caesar, and Publius Servilius Casca, a childhood friend of Caesar, began stabbing him. Caesar reeled in shock and said, “Scelerate Casca, quid facis?” Caesar bled to death on the floor of the Senate after being stabbed by the group of senators 23 times. This was the end of the Roman Republic and the beginning of the Roman Empire.

There were 60 conspirators associated with the assassination of Julius Caesar. Remarkably, only 20 or so are known. Their motives were the typical ones of politicians, a combination of best intentions and to resolve personal grievances. The killing was done in public, so there was no doubt that it was done with the idea and hope that it would be seen as saving the Republic from authoritarianism — Caesar had been made dictator for life. But the opposite was the case; the murder of Julius Caesar, intended to return the Republic’s constitution of checks and balances, instead was the blow that ensured its demise.

The Fall of the Roman Republic as Analogy to Our Own Political Moment

We seem to be in a similar phase of our republic in the United States; there is one individual that seems to be testing every limit of the written and unwritten constitutions taken for granted for generations. Each and every effort to contain, control, or confound his seemingly boundless energy for controversy seems only to make the problem worse. Donald Trump is no Julius Caesar, but are his opponents like his assassins?

Drawing analogies between current events and moments in history is often seen as dubious. There are two camps on the practice, as Hugh Trevor-Roper describes so well in the opening of his biography of Archbishop Laud. For many, figures of the past bear no resemblance to the people and their natures today. This camp, Trevor-Roeper wrote, finds “the actions of men appear to have followed rules entirely different from those with which the modern world is familiar.” Different people in different times are simply, well, different. To compare them is “superfluous.”

“To some people, to those sentimental persons,” continues, showing his bias, “who find in the past not a variation of the present but an escape from it, this interpretation is perfectly satisfactory. But it cannot easily satisfy those who seek in history not romance but instruction, and who believe, as an historical axiom, that human nature does not change from generation to generation except in the forms of its expression and the instruments at its disposal.”

What instruction can we draw from the fall of the Roman Republic at the hands of those who were so desperately trying to save it? The United States was not unique for its revolution – the English had already executed their king and replaced him with a Commonwealth more than a hundred years before the Declaration of Independence was signed – but it was unique in its self-conscious efforts to recapitulate models of governance from the past both near and distant.

One scholar points out that the authors of the new country’s written constitution realized that “not only was Rome’s Republic remarkably successful, but it was remarkably well-suited to the kind of project that the founders were imagining in the United States. That’s because Rome’s was a republic that, as it expanded, incorporated representative democracy.”

The Roman Republic: What Was It and How Did it Function

Rome was not always an empire. There were three phases of Roman history, the first beginning in 753 BC with the legendary founding of Rome by Romulus which began a period call the Rule of the seven Kings of Rome. This period was marked by a series of kings of various reputation, but ended with the reign of a very bad king, Lucius Tarquinius Superbus who was arrogant and violent, abusing the Senate, nobles, and the populous. His overthrow led to the formation of what became the Republic around 509 BC.

Romans disliked the notion of kings and the rule of one man. It might seem strange that when most people today consider Rome they think of the Empire, a period of gladiators in the coliseum and emperors with absolute power. But that memory of Rome represents less than half of Roman history. Many of Rome’s great accomplishments of conquest and culture were achieved while it was a republic.

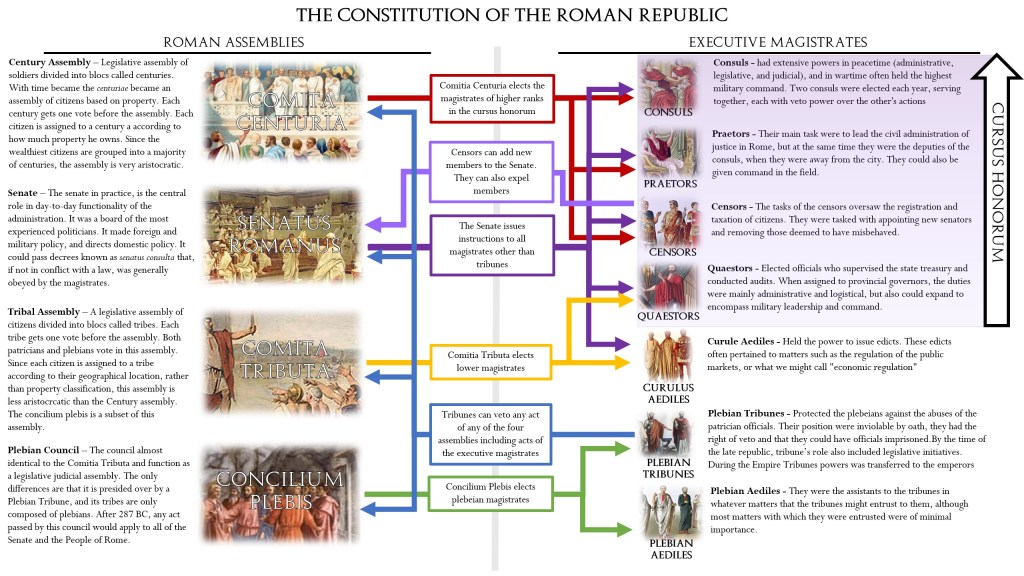

The constitution of the Republic was unwritten and was complex, consisting of both assemblies and legislative bodies and magistrates with executive power.

While class mattered – only the wealthy and high born could pursue the cursus honorum that lead to the highest executive offices – there were powerful offices created specifically for the plebian or lower born classes. These interests were balanced against each other in surprising ways: plebian tribunes could veto and vex initiatives from the legislative bodies, including the senate. The tension in the system resulted in power never aggregating in one place or one person. Like any constitution, precedent was powerful; a consul, the most powerful office (think President of the United States or Prime Minister) could run for reelection after one-year long term, but almost nobody ever did.

Throughout the period of the Republic, many strong personalities and power centers emerged, but it would have been unthinkable to attempt to take and keep power. The system was set to limit and slow change. During war or when Rome was under attack, these norms could be suspended, but when the threat diminished or was ended, the expectation was that the power of a great general would slacken and the normal order would return.

The Fraying of the Republic’s Constitution

An American audience, unfortunately, possesses a very particular sense of what a constitution looks like. To them, it is a document, and even worse, most Americans believe that the Constitution of the United is unique and reification of the ideal of democracy. On the contrary, even the American Constitution has the significance of the by-laws of a Home Owners Association; it lays out the basic rules of governance and offices held to execute the functions of government.

What most people think when they think of something’s constitutionality is not what is written down, but the nature of the norms and expectations beneath, around, and in-between the words. The “magic” so to speak of a constitution abides with the relationships it inspires. For example, there were no term limits for Presidents when George Washington left after two terms, and that norm was not broken for 150 years. Norms like standing for the President when he walks into the room, Prime Ministers stepping down when the lose the confidence of their own party, or generals avoiding political endorsements are the sorts of things that form the fabric of a functioning constitution.

Rome is perhaps the earliest example of an intentional establishment of these sorts of norms, and they were based on generally accepted values called mos maiorum; the English word mores is derived from mos maiorum. The mores that were often articulated by Cicero were fides, trustworthiness, pietas, respect towards the gods, homeland, parents and family, cultus, religious practice, disciplina training, discipline and self-control, gravitas dignified self-control, virtus, virtue or manhood, dignitas, reputation, prestige and respect.

Joana Kenty in Congenital Virtue: Mos Maiorum in Cicero’s Orations does a quantitative analysis of the nature and number of Cicero’s influential pronouncements on maiores and their relationship to life and policy. One particular reference will sound familiar to most Americans.

“In Republican Rome as now, laws were susceptible to multiple conflicting interpretations, and one criterion for judging their relative legitimacy was their compatibility with the original intention of the legislators or precedent-makers. The maiores are therefore also recruited as the source of what we would call the spirit of the law as well as of the laws themselves. Because of their importance as Rome’s original policy-makers, by far the most common verb used with maiores in the orations is volo (or nolo), in the sense of the ancestors “wanting” or “intending” a particular practice or effect (40 examples). According to Cicero, their will dictates that the law courts should be a publicum consilium.”

There is almost never a debate over the American Constitution that doesn’t sound like this: what was the intention of the Founding Fathers and does that matter in today’s world? At its height, the Roman Republic, though more than 2000 years distant, had a system of government that is highly recognizable to most modern residents of so-called Western democracies.

Tiberius Gracchus: The Beginning of the End?

The drama and controversy surrounding the plebian tribunate of Tiberius Gracchus in 133 is often cited as when the Republic began to unravel. It is a time and Gracchus is a figure that must be taken into account when considering the end of the Republic.

Gracchus was born in 163 BC, the son of a well-established family; his grandfather was Scipio Africanus, the general who dealt a final defeat to Hannibal in the Second Punic war. Gracchus seemed to be on his way to obtaining the dignitas a young man in his position would need to seek in the competitive Roman society when he was sent to Spain to subdue the Numentines. Having started his path down the curus honorus he was made quaestor in 137 and attached to the wonderfully named general, Gaius Hostilius Mancinus, he hoped to add to his already growing list of military achievements in the Third Punic War against Carthage.

The campaign against the Numentines did not go well, and soon, Mancinus and his army were trapped without reinforcements. Surrender was unthinkable, but to fight on meant certain destruction. Mancinus wanted to negotiate a treaty, but the Numentines refused unless they could work with Gracchus. Previous treaties had not been honored, and the Numentines had bargained successfully before with Gracchus’ father, also named Tiberius. While Gracchus was successful, when he and Mancinus arrived home, the Senate was outraged by the terms and rejected the treaty. This was a blow to Gracchus’s virtus and dignitas.

There is reason to believe that this stumble would slow or stop Gracchus’ climb to higher offices and to more military commands. Surrendering was bad enough, but Gracchus could be reasonably blamed for the unfavorable and perhaps humiliating terms. He couldn’t blame Mancinus for his poor leadership since it was, he, Gracchus, responsible for not only negotiating a bad treaty, but not fighting to the death. Gracchus managed to avoid the consequences of the treaty and was later elected plebian tribune.

At the time, Rome was experiencing the impacts of its conquests. Much of the land it gained was deposited in what was called the ager publicus, public land. This land however was not managed effectively, and often wound up in the hands of wealthy families. Farmers who did own land typically divided their land when they died among heirs, and parcels grew smaller and smaller until they were useless. As the population grew with more acquisitions, many left the countryside and came to Rome. With an oversupply of labor, and food distribution issues, poverty rose. While ownership of land was supposed to be limited, the rules were widely ignored, and other families accrued more and more land.

As plebian tribune, Gracchus took a land reform proposal, the lex agraria, directly to the Assembly without stopping by the Senate. His intention was to enforce the existing requirements, return the land to public use, then redistribute it to poorer families. Those without land in both the city and the countryside welcomed the reform, while families that had expanded their use of land into public land opposed it. The proposal was vetoed by another tribune, Octavius. Stymied, Gracchus attempted to have Octavius removed from office, something that violated established norms. That violation was extended when, by some accounts, Octavius was dragged out of the Assembly and the law passed without him present.

The Senate refused to grant funds to implement the law and Gracchus was threatened with prosecution. To shield himself against that – magistrates had immunity from any prosecution – Gracchus decided to seek another term as plebian tribune, yet another violation of norms.

It is more than 50 years old, but M. M. Henderson’s article, Tiberius Gracchus and the Failure of the Roman Republic is an efficient and engaging take on the question of whether and how the tribunate of Gracchus was indeed the place when the Republic began its descent down from its height as a society with balanced government. Henderson describes what unfolds next. After Gracchus’ candidacy is vetoed,

“The opposition in the Senate, hearing an exaggerated report, concluded that Gracchus was resorting to violence to secure re-election. Scipio Nasica, failing to gain the support of the Consul (who was a pro-Gracchan) ‘sprang to his feet and said: “Since then the chief magistrate is betraying the State, all who wish to succor the laws follow me,” ‘ – and led the opposition, armed with broken bits of benches, to the assembly. The fact that Nasica’s supporters were not already armed with knives shows Gracchus; their prevent his re- disturbance before this we cannot tell. What is certain is that the arrival of Nasica and the armed Senators in the assembly provoked a bloody riot in which Gracchus and many others lost their lives.”

Generally speaking, I think a sustainable view of where the Republic began to fall apart, is that pressures of success began to tax the structure of the Republics economy and thus its constitutional balance of power. For a long time, wealth and land piled up among one class, while another saw few gains. The system of closely calibrated tensions, unwritten understandings, and creaky traditions began to break under the needs to reform the system. Gracchus, according to Henderson, was not alone in the view that public land should be distributed in a way to relieve those tensions, especially to move poor and restless people out of the city and into the countryside.

Lex agraria was also popular, appealing to Gracchus’ constituency; he was the plebian tribune after all. After the Numentine fiasco, Gracchus might have seen the reform as a path back toward the consulship. Gracchus was like any other politician, seeking to appeal to the masses while climbing the ladder toward more power and dignitas. And it is important to remember who Gracchus was, the grandson of Scipio Africanus, one of Rome’s greatest heroes of the time. Gracchus’ mother was known to have high expectations of her sons, and the pressure to fulfill the expectations of pietas would have been strong.

Henderson challenges the view that Gracchus was either self-consciously or in effect a revolutionary.

“Tiberius Gracchus was not set upon revolution. Tiberius, far from being a philosopher trying to foist alien ideas upon Rome, was very much a practical politician of his time. His methods . . . had been tried before. In these he was unexceptional. In his end he was not.”

Henderson’s view reminds me of A. J. P. Taylor’s controversial view of Hitler in his clear-eyed view of the Origins of the Second World War.

“The elaborate plot by which Hitler seized power was the first legend to be established about him and has been the first also to be destroyed. There was no long-term plot; there was no seizure of power. Hitler had no idea how he would come to power; only a conviction that he would get there. Papen and a few other conservatives put Hitler into power by intrigue, in the belief that they had taken him prisoner. He exploited their intrigue, again with no idea how he would escape from their control, only with the conviction that somehow, he would. This “revision” does not “vindicate” Hitler, though it discredits Papen and his associates. It is merely revision for its own sake, or rather for the sake of historical truth.”

Taylor, one of the great if not the greatest historian of the last century, was perhaps too defensive. His debate with Hugh Trevor-Roper was easily won, but his reputation suffered anyway. Too close to the events, historians were expected to validate common wisdom about what had just happened from a moral sense, in the sense of sorting out winners and losers.

I lean in Taylor’s direction and in Henderson’s too. He explains that,

“The crisis of 133 hinged upon the fact that one political group was making a bid for power, based on a scheme which might be of immense benefit to Rome; while another political group – indeed almost all the other nobles – could not afford to let this happen and were determined to stop it at all costs.”

By 133, families and parties arrayed against one another not for ideological reasons but for power. And perhaps it is true that this was an erosion of mos maiorum brought about by crushing Carthage, a counter force in the Mediterrian that was truly an existential threat to Rome, and the subsequent wealth that flowed into Rome when it stood alone as a world power. It might be satisfying to cast Gracchus as an early communist.

Henderson puts the blame in the right spot: the Senate. The institution’s participation in the murder in the streets of Rome of a tribune presages the death of Caesar and unleashes forces that cannot be restrained. In the name, perhaps, or restoring the order upended by Gracchus testing of the limits of the constitution, the Senate itself began its own undoing. Henderson’s closing words that echo the opening of Lucan’s poem (Loeb),

“I tell how an imperial people turned their victorious right hands against their own vitals; how kindred fought against kindred.”

And Henderson.

“The decline in the reputation of the Senate is directly attributable to the way the opposition behaved during the tribunate of Tiberius Gracchus. Increasingly opposed, it lost control of events until those armies, on whose loyalty the Senate depended, defected to individuals and brought an end to republican government in a bloodbath of civil wars.”

After Gracchus: Dictators and Civil Wars

The next 90 years are summed up well by R. H. Barrow in The Romans,

“The age that follows is the age of great individuals seeking so to alter the machine of government as to adapt it to the new stresses, yet patiently preserving, as far as they could, the old component parts. But impatience frequently prevailed, and impatience was fanned to white heat by the personal rivalries which followed upon the competitive claims to adjust the government to satisfy ambition or the claims of faithful armies.”

One important feature of the Roman army in the Republic was that soldiers had to pay for their own equipment and costs to go to war. The only way they could do this was if they owned land. Land and military service were bound together in a way that added to the pressures on maldistribution of land resources. Poor people couldn’t serve and get the benefits of service, and those who did have land, often had to give it up for service in hopes of gaining from war. The reforms of Gaius Marius changed all that in 107. Among other things,

“Marius secured the rights of the poor to enlist in the Roman army, which they hadn’t previously been permitted to do because Roman soldiers had previously been required to provide their own arms and armor, which the common people simply didn’t possess enough money to purchase. In order to make this reform work, Marius also standardized the equipment that Roman soldiers were to use while on campaign and ensured that his new army would provide each of its soldiers with said equipment.”

This did two things, create a standing army which Rome had never had, and attached poor soldier’s fate to their generals. Recruitment didn’t require any cost, and victory in battle and war was a path out of poverty. Previously, going to war was part of mos maiorum, a kind of mystical and practical connection to something greater including the constitution. Now, military service was detached from that and attached to great generals. The very symbol of the Republic was the acronym, SPQR, Senātus Populusque Rōmānus or the Senate and People of Rome. The symbol would persist, but the connection would not.

Lucius Cornelius Sulla, born in 138, was a quaestor under Marius from 107, and would be the first “great individual” to rule after the first of Rome’s civil wars. It began in 88 when an aging Marius was inexplicably appointed to an unprecedented 7th consulship and appointed commander of a military expedition to Greece to squash an uprising by Mithradates. By this time Marius was aged and senile and Sulla rejected the Senate’s decision to take away his command; Sulla did something no general had ever done, march his army threateningly toward Rome. Marius countered this, and for the first time the Republic had open warfare between two factions. In the end, Sulla would win and be appointed dictator for life, a pattern roughly followed by Caesar later.

Sulla ruled as a strongman, abrogating the typical function of the constitution. Yet, he thought of himself as a republican, and while ruling absolutely attempted to permanently establish the authority of the Senate. Sulla used Marius’ reformed army to tame enemies in Greece, but as Barrow emphasizes, also

“To enforce upon Rome what it had never had before, namely a written constitution and the legal recognition of the supremacy of the Senate. He then stepped into retirement to watch his constitution work.”

By this time, however, a pattern had begun of “impatience” followed by action, force, and violence to resolve the issue. Before, disputes worked their way through the multiple branches of legislative bodies and magistrates. No more. When something wasn’t working, the constitution was set aside in order to preserve it. When Pompey, a deputy of Sulla, began to rise, indecision or opposition was countered by men who could back their point of view with muscle and force of loyal soldiers.

The Rise of Julius Caesar

It’s easy to think, for me anyway, of Julius Caesar as a lifelong soldier, who, frustrated like Sulla with bad decisions by the Senate, crossed the Rubicon to put an end to it all and establish himself as the first Emperor. This was not the case. Born in 100, the son of an aristocratic family that claimed their descent from Aeneas, Caesar was pursuing the consulship along the cursus honorum the same way Gracchus had. He chose political and religious offices, including the highest religious office, pontifex maximus, and was an effective and successful politician, challenging and surviving the reign of Sulla and coming out the other end of that period with allies from both sides.

Caesar made his bid for the consulship in 59 BC, with support from Marius’ allies, Sulla supporters, and an endorsement from Pompey. His efforts to promote reconciliation post-civil war gained approval from various societal levels. He was elected with consul to serve with Marcus Calpurnius, a political foe, but Caesar was seen as a conciliator between factions in the civil war. Later, Caesar would combine his consulship with that of Pompey and Crassus forming what is commonly called the First Triumvirate and the relationship that would lead to the next civil war. But before that, Caesar led a force to Gaul and campaigned against the locals there from 58 to 52, writing his Commentaries on the War in Gaul which has the iconic opening, Gallia est omnis divisa in partes tres. They were also delivered regularly to the populace back home, making Caesar a well-known war hero.

Beginning in 52, trust between Pompey and Caesar fractured and as tensions grew their armed camps were poised to begin fighting. In spite of efforts to disarm both groups, moves to recall Caesar from Gaul continued in the Senate. Julia, Pompey’s wife and Caesar’s daughter, died and Pompey grew more wary of Caesar’s growing ambition and popularity. As Pompey grew closer to the Senate and suspicions grew about Caesar’s next move, the Senate issued a Senatus consultum ultimum, a final call to reign Caesar in and deem him a threat to Rome. For his part, Caesar wanted to be reelected consul because with that election would come immunity. He refused to comply with the Senate until this was resolved.

Conventional wisdom is that the Caesar’s concerns about being prosecuted and maybe executed drove him to march on Rome as Sulla did. Finally, after considering it, on January 10, 49, crossed the river Rubicon with the famous phrase, Ālea iacta est. This began an extended conflict with Pompey and his forces which culminated in Caeser’s victory at the battle of Pharsalus after which Pompey fled to Egypt and was killed. It would only be four years later until Caesar would lay dying on March 15 – the Ides of March – in 44.

Why Did the Republic Fall?

Rome stands out in the ancient world but in all of history as unique for having constructed, self-consciously, a system of institutional conflict that diffused power among various bodies and offices. Also unique was the Roman aversion to Kings and power concentrating in a single individual. Why would such a progressive – to use a contemporary term – system have failed?

- Exception not the rule – The uniqueness of the system is one answer. Throughout history, most large and growing societies have relied on strong central governments and strong decisive leaders for better or worse. The Roman constitution was pushing against deeper human tendencies toward strong leadership during times of conflict and crisis.

- End of the Punic wars – When Rome finally and completely eliminated its main rival and existential threat, Carthage, the absence of an external threat exposed internal divisions.

- Turning inward – Fractures between classes, long ameliorated by continued outside threats from Carthage, were now exposed and the system was not prepared to deal with them efficiently.

- Poor distribution of resources – As the population grew along with more territorial responsibility and wealth, the Roman economy failed to adequately distribute resources. This isn’t a criticism of capitalism, as anachronistic as that may sound. Economies of all kinds, at all times and places, must distribute resources well; if they don’t, underlying social, cultural, and even personal conflicts can grow and burst into violence.

- Erosion of mos maiorum – Instead of deeply held values, as conflicts grew and the system failed to deal with them, people became more dependent on being on the winning side, forced to align with various generals and strongmen.

This question has been debated for 2000 years, including by historians and writers of the time. It is a deep subject, and obviously my treatment of it here is shallow. Yet, it is informed by a broader sense and knowledge of history and politics. Understanding the Roman Republic in context, as an example, and an analog is worthwhile for debates about history, politics, and current events.

Prologue: A Political History of the United States

It’s important take a look now at the United States. As I have already pointed out, the American Constitution as a document, has very little value by itself other than a set of rules of basic governance. The real constitution is a deeper document, written, in part, on people’s hearts and in their minds, but also the product of generations of shared culture and history continually evolving over time. But the United States were not formed in a workshop in Philadelphia but rather grew from roots in the British Empire and England.

The English Civil Wars

The American “experiment” as it often is called, certainly was also a deliberate effort to recapitulate the institutional balances of the Roman Republic. But it was also deeply embedded in the history of the previous 150 years, which included a civil war in England that resolved itself in a system of checks and balances enshrined in an unwritten constitution.

The role of the land and it’s use and misuse can’t be underrepresented here. There are similarities between the role land played in the collapse of the Roman Republic into civil wars, and the English Civil wars, both as a practical driver of dissent and division, but also as symbolic of a transformation of economy and society. Briefly, common land used by commoners to hunt, forage, and graze their animals was frequently enclosed by the King’s government. The enclosures meant a loss of entitlement and livelihood. With the reformation, the common sense of who could make such decisions was expanded; people were activated to question the absolute nature of rule by kings.

The English Civil Wars are as complex, of course, as the Roman ones, but put simply, friction between a monarchy still clutching on to the middle ages was increasingly in conflict with a parliamentary system that was born out of the rise of the Tudors. Because of the shaky claim to the throne by Henry VII, which he took by force, all the Tudors grew more and more dependent on Parliament for legitimacy. That institution has ancient root in Magna Carta, a document produced in the 13th century as a resolution to a conflict between the Barons and aristocracy and the King. However, Magna Carta became much more than that, indeed something not unlike mos mairoum. When Americans are asked, “What it means to be an American?” they will likely cite, freedom of speech, freedom from search and arrest without warrant, and trial by jury, all things with deep roots in Magna Carta.

By the succession of Charles I, the friction between growing religious plurality – fueled by Henry VIII’s embrace of the Reformation through his break with Rome – and economic expansion and growth, began to test and stress the relationship between the monarchy and Parliament. Charles was an absolutist, and when, in 1629, Parliament attempted to assert itself on issues of taxation and arrest with the Petition of Right, Charles dissolved it and ruled without it for 11 years, until he was forced to call it back into session. What followed was an iconic scene, the King’s entrance into Parliament in January of 1642 to arrest some of its members. Parliament refused to hand them over, and Charles again dissolved the body. Just seven years later, Parliament executed him and dissolved the monarchy.

The Glorious Revolution

Even after the establishment of a Commonwealth, its collapse, and the restoration of the monarchy, constitutional stresses and tensions did not abate. If anything, the succession of James II, a Catholic married to a Catholic queen only made matters worse, particularly because, unlike his brother Charles II, James insisted on pushing for more rights for Catholics. When, in 1687, James issued a Declaration of Indulgence for Catholics in England, and demanded that it be read from every pulpit in the kingdom, 7 Bishops refused to comply. Their subsequent trial and acquittal resulted in James fleeing the country, essentially leaving the throne vacant.

The aristocracy and the Parliament, rather than finding themselves at that moment in 1688 on the edge of another civil war, came to consensus and called William, the Prince of Orange of the Netherlands and his wife, Mary, the daughter of the departed King James II. The document affirming their reign was created in the form of an Act of Parliament was called the Bill of Rights and was passed in 1689. That document bears a strong resemblance to the Declaration of Independence, outlining the abuses of James II then declaring and “vindicating and asserting their ancient rights and liberties.” That is followed by an oath required of William and Mary requiring them to repudiate the papacy and an articulation of protections for the members and functions of Parliament.

While hardly a written constitution, the Bill of Rights functioned as a sort of contract between the monarch and the legislature to limit and prevent the sort of specific abuses of the rule of law by both the Stuarts, the Parliamentarians during the Civil Wars, and Cromwell during the Commonwealth. This settlement secured the dominance of the Parliament over the monarchy, and in subsequent generations was shaped as part of England’s unwritten constitution as the Glorious Revolution through Whig History, a view of the ascendency of British values promulgated by Baron Thomas Macaulay.

When American revolutionaries gave the rationale for breaking from Great Britain in the Declaration, they based it substantially on George III “abolishing the free System of English Laws” and attempts to introduce “absolute rule into these Colonies.” What’s perhaps ironic, is that for most American’s the central narrative of the American Revolution is the throwing off of an absolute monarch; George III was nothing of the sort and there hadn’t been an absolute monarch in England since at least the execution of Charles I. Arguably, in England there hadn’t been an absolute monarch since King John signed the Magna Carta in 1215.

The American Constitution

For the purposes of this exercise, it’s essential to discuss the American Constitution both written and unwritten, although such a task can only be done the way one throws the light of a flashlight around a dark room. Some of what I am going to suggest won’t be cited with sources here but is done to make the comparison and then the point. But as I indicated earlier, the American Constitution is much more than the written document with its amendments, but a panoply of values that have some consensus and some others that have none.

One only has to look at the buildings in the nation’s capital to see the explicit references to the Roman Republic. The founders were trained in the classics, and when they had successfully secured a break from Britain, they did what they could to create a system that would match the idealized views of the Roman Republic. An useful article by Steele Brand, Why knowing Roman history is key to preserving America’s future, points out the many important connections the founders made to the Roman Republic’s constitution.

“This Roman influence was crucial, because a very different path presented itself at the time the Founders were designing the United States. The French Revolution took a different course than its American counterpart. It did not simply seek to rebalance power but rather to eradicate all existing power bases. The revolutionaries overthrew everything: the monarchy, the church, the nobility, property rights and most of the other things that had held the French people together for centuries. The result was total anarchy fueled by bloody purges of whoever happened to be on the wrong side of the revolution, which was constantly changing in the 1790s.”

The American Revolution was a very conservative one, which is why Edmund Burke supported it as a member of Parliament but reviled the French Revolution. The Americans didn’t try to duplicate the various offices of the Roman Republic, but instead, recapitulated the ones they were most familiar with, monarch, House of Lords, and the House of Commons which became the Presidency, the Senate, and the House of Representatives. What they tried to keep was the very deliberate tensions between the houses of the legislature, the executive, and the judiciary. Change can happen under the Constitution, but it can’t happen quickly. Changes can’t be made by one person or one institution, but it requires a leavening process. And change doesn’t require consensus, but it does require compromise.

The First American Civil War

The Constitution faced its first test over resources in the nullification crisis of the 1830s. The federal government had passed tariffs that favored northern manufactures over farmers in the south. These taxes passed through the system successfully, yet southerners still resented them. The country was new enough, that many people remembered that to form it, individual states had to join. Many people, especially southerners, identified more strongly with their state than with the United States. Why should individual states have to accept the dictates of the federal government? Nullification was the idea that a state could opt out of federal taxation or other directives it didn’t like.

Thomas Jefferson supported this concept, supporting in favor of efforts by the state of Kentucky to not follow the Alien and Sedition Acts of 1797, writing that “where powers are assumed which have not been delegated . . . a nullification of the act is the rightful remedy.” The other side of this argument was that the supremacy clause of the Constitution meant federal laws were binding on states unless a court found them unconstitutional. The issue eventually abated, but it never went away, growing worse and worse around the issue of slavery.

The American Constitution showed the same weaknesses as the Roman constitution, except that the Roman system was not written down in a static document. Neither was the English constitution. The American’s wrote their system of checks and balances down which meant that allowing flexibility was impossible. States could either nullify federal laws it didn’t like or they couldn’t; there was no room to evolve a response to the tension. The brittleness of the Constitution was apparent in less than 50 years after it’s creation.

By 1860 rural slave states in the south no longer wanted to be part of the Union. They chose to join the Union, now they argued, they could choose to leave. But splitting the country in two was not acceptable to the north, so a massive and destructive war ensued. While the south lost the war, the cultural and social friction remained. Even after the official end of slavery, legally enforced segregation, lynching, and other abuses remained in southern states for another 100 years, well into our own time. Today, political differences in the country track very closely to the boundaries of the confederacy, and red and blue states are usually defined by their rural or urban communities respectively.

The founders admired the Republic and baked into their Constitution not only tensions between regional economies, class, and party, but placed almost unreachable thresholds to make substantial change. Many in the country are at each other’s throats over gun ownership for example, but to change the Second Amendment is an impossibility. With every school shooting or other gun involved tragedy, the same tensions underlying the first civil war flair up; should people be forced to live with federal laws they don’t like or see as an existential threat.

The Analogy: “Are we rolling downhill like a snowball headed for Hell?”

In today’s America, it’s hard to read or watch any news without hearing the phrases, “this is unprecedented” or “nothing like this has ever happened” or “our democracy is being threatened.” Both left and right use this language ceaselessly. It’s worth remembering Barrow’s description of the Republic after Gracchus,

“But impatience frequently prevailed, and impatience was fanned to white heat by the personal rivalries which followed upon the competitive claims to adjust the government to satisfy ambition or the claims of faithful armies.”

We don’t have armies, but we do have CNN and Fox News. With each and every shock, Americans seem to become inured, numb and the internet and social media need to be dialed higher and higher to get the shock; politicians shed decorum and nuance in favor of heckling and shouting at each other. That unwritten glue between the words of the written constitution seems to be dissolving. People on both sides talk of what sounds like nullification if the other side wins the election.

The American Civil War might have ended on the battle field in 1864 but it is still being fought at kitchen tables, board rooms, classrooms, and in the media day after day. What accounts for this latest upswell in the deep underlying tensions welded into our body politic by our Constitution?

- Exception not the rule – Like the Roman Republic, we’re fighting history and human nature. While the founders sought to emulate the Roman Republic, they seemed to have forgotten how the structural weaknesses and brittleness of checks and balances would lead groups and factions to going around the Constitution to find a way to win.

- End of the Cold War – After the end of World War II, the United States saw itself as the defender of freedom in the world, standing against and existential threat, the Soviet Union. When it was finally defeated like Carthage was, the United States no longer had an enemy to unify against.

- Turning inward – As in the Republic, fractures between classes, long ameliorated by the outside threat from global communism, were now exposed and the system was not prepared to deal with them efficiently. Over the last thirty years, what seemed like progress on many social and cultural issues has eroded.

- Poor distribution of resources – As with the Republic, this is not a critique of capitalism. But take housing for instance. Local intransigence has regulated housing supply to make it scarce and expensive. But instead of expanding supply by loosening rules, government adds more, many of them punitive to punish people who build and manage housing. This makes the problem worse.

- Erosion of mos maiorum – That an evangelical Christian could support Donald Trump or that a Democrat who voted for Bernie Sanders could by sympathetic with the FBI and CIA are indications that once deeply held values have been abandoned in favor of prevailing in a battle of personalities and reprisal.

To bring the analogy home, I’d compare the killing of Tiberius Gracchus to the assassination of John F. Kennedy. America had three previous Presidents killed in public, but never had so many seen violence against a leader so vividly. The violence of the Vietnam War was brought home on the evening news for years. Then Nixon was almost impeached. The Saturday Night Massacre – when Nixon fired the special prosecutor investigating him – was called a “constitutional crisis.” Nixon resigned. That had never happened. And the list goes on.

These extraordinary events have continued in intensity and frequency, but the country seemed to manage a devastating terrorist attack in 2001, a botched election the year before, and two wars in the Middle East without the kind of tension that has become common today. The country seems to be headed for a crossroads.

A Warning From the Republic

Donald Trump has just gained the Republican nomination for President for a third time in a row. Yes, this has never happened. It is unprecedented. He may be convicted for a crime before the election. And it is entirely possible he will win. If he doesn’t, it is certain that his followers will believe the election was stolen. If he wins, his opponents have said that it will have been the last free election Americans will have voted in. Neither side has left any room at all for any accommodation for an adverse outcome.

This is problematic to say the least. In his book, The Last Assassin: The Hunt for the Killers of Julius Caesar, Peter Stothard tells the story of the last assassin of Caesar, Claudius Parmensis, who was finally hunted down and killed in Greece years after the killing. Stothard asks the obvious question of the assassins,

“To what extent were you justified in getting rid of a tyrant? How bad did a ruler have to be before you were justified in committing the country and half the world to civil war?”

Ron Desantis was closing in on Donald Trump early in 2023 in the polls for the Republican nomination. Then, according to a CBS news summary, “Trump was indicted in four separate criminal proceedings — facing a total of 91 felony charges. With each indictment, Trump saw a boost in his primary poll numbers and was able to raise millions off of perceived efforts to unfairly target the former president.”

What will his opponents do if all the charges and legal efforts fail to keep him from leading in the polls? What if he wins? If it is true as Liz Cheney says that democracy in America will end with Trump’s reelection, what are the obligations of those who want to save the Constitution. Men like Claudius Parmensis took it upon themselves to solve the problem.

Caesar was not the problem. The problems of the Republic have been discussed. It was those issues, poor distribution of land, a standing army aligned more with generals than with common values, that lead to chaos and disruption. Trump isn’t the problem either, he is a symptom. The more he is pursued, the more it validates his claim that he is being pursued. Brand warns, “A republic can endure many things, but a citizenry ignorant of the past dooms it to failure.”

But history is so boring and “superfluous.” The only answer is to stop. Stop pursuing Trump, stop reading about Trump. That would have worked 9 years ago. But maybe it’s too late.

I can hear the repeated phrase in Mark Antony’s funeral speech from Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar.

“And Brutus is an honorable man.”

——————