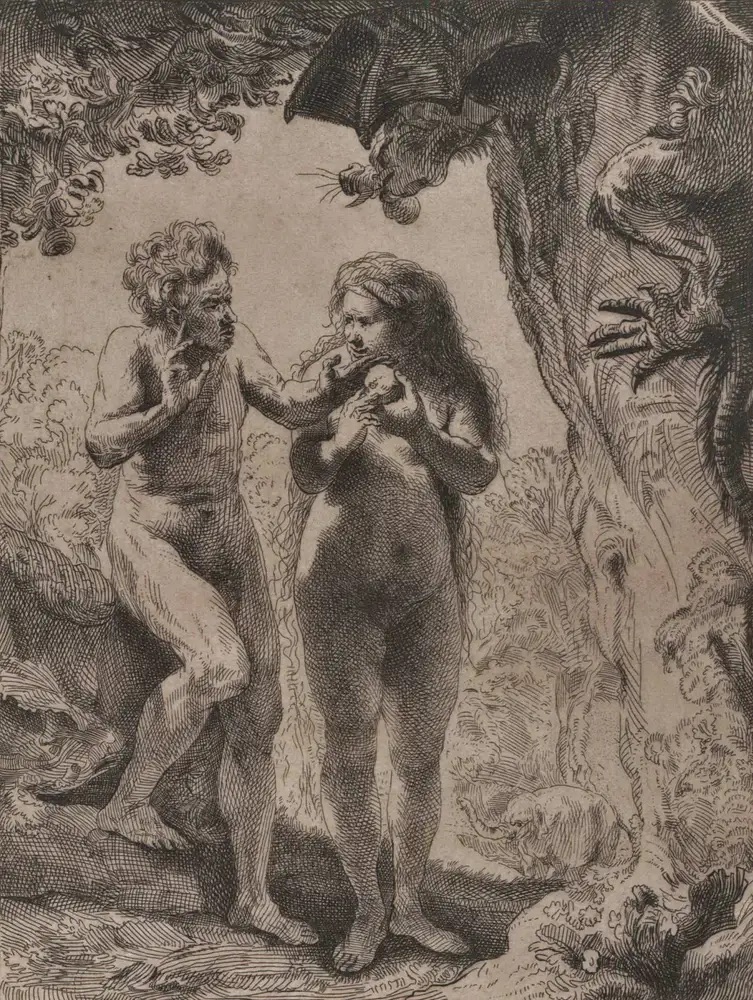

One of my favorite passages in Latin is from Giovanni Boccaccio’s Famous Women, his encyclopedic effort to write the stories of great women in literature, alive, and dead. He starts appropriately with Eve, describing her in what I’d consider heroic terms.

Nam, non in hac erumnosa miseriarum valle, in qua ad laborem ceteri mortales nascimur, producta est, nec code malleo aut incude etiam fabrefacta, seu eiulans nascendi crimen deflens, aut invalida, ceterorum ritu, venit in vitam

Virginia Brown renders the Latin this way in her translation.

“She was not brought forth in this wretched vale of misery in which the rest of us are born to labor; she was not wrought with the same hammer or anvil; nor did she come into life like others, either weak or tearfully bewailing original sin.”

Eve began our great adventure by seeking to share knowledge. Eve “broke the law and tasted the apple of the Tree of Good and Evil,” Boccaccio reminds us. Adam was warned, and we see a connection between knowledge and death in Genesis 2:17.

“You may surely eat of every tree of the garden, but of the tree of the knowledge of good and evil you shall not eat, for in the day that you eat of it you shall surely die.”

But knowing was worse than death because “they brought themselves and all their future descendants from peace and immortality to anxious labor and wretched death.”

Why do we have such a thirst for knowing. We’re curious creatures. But we’ll often go to great lengths just to know. And is knowledge power? Does it truly give us what we think it can?

A fellow graduate student told me, “omniscience presupposes omnipotence.” Does knowledge condition free will? Knowledge and will are strongly correlated. These questions will be my subject.